|

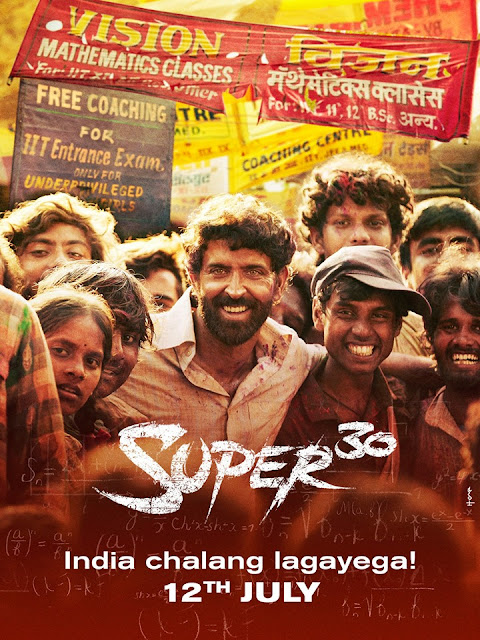

Release

date:

|

July 12, 2019

|

|

Director:

|

Vikas Bahl

|

|

Cast:

Language:

|

Hrithik Roshan, Mrunal Thakur,

Pankaj Tripathi, Sadhana Singh, Virendra Saxena, Aditya Srivastava, Vijay

Verma, Amit Sadh

Hindi

|

From a Hindi film industry that has

for decades now barely acknowledged the existence of India’s caste system, it

is quite something to see two films rooted in caste discrimination – Article 15 and Super 30 – within a span of a fortnight. Let us take a minute to

celebrate that change.

The question now is this: should

we be so grateful to artists who bring up issues rarely visited by their

colleagues that we let their faux pas, prejudices, poor research and poor

storytelling pass? Or do we call them out on their follies in the hope that they

are genuinely invested in their chosen themes, and will try to do better next

time?

The answer is: say it like it is. Of course a star

as major and glamorous as Hrithik Roshan opting to play a character from a

lower caste is a turning point in this insular industry which has long assumed,

as it once did about women protagonists, that heroes from marginalised

communities can only yield tragic weepy tales that have no place in the

mainstream. What is lovelier still is that Super

30 is based on the uplifting story of a real-life achiever. That it comes

to us at a time when any critique of caste is slammed as being

“Hinduphobic” makes it courageous too.

No doubt these are laudable

starting blocks. But Super 30 dilutes

itself in multiple ways. First, the brown makeup used on Roshan for the role of

Anand Kumar signals a stereotypical understanding of what it means to be lower

caste, offering us Hindi cinema’s caste equivalent of the white Western world’s

brownface. “He doesn’t look Dalit” was a criticism levelled at Prakash Jha for

casting Saif Ali Khan as a Dalit in Aarakshan.

Those pointing fingers should have told us what that “look” is since Dalit is

not a race or ethnicity but a pan-India social categorisation signifying

extreme ostracism and a forced adherence to certain professions. If Team Super 30 was indeed convinced that

Hrithik’s light complexion would never be found on a member of a lower caste,

it is worth asking why they did not go in search of a dark-skinned actor

instead of bottles of brown make-up, because the caking up of a well-known face

is distracting, to say the least. And if their argument is that all they wanted

was for Roshan to resemble the man he is playing as closely as possible, well

then, videos and photographs of the real Anand Kumar will tell you that he

looks nothing like the Bollywood hottie with or without makeup, so that claim

does not hold water.

Second, while Super 30 is gutsy off and on with its

caste references, it is also simultaneously hesitant in addition to betraying a

limited understanding of this deeply entrenched social dynamic.

So, bravo for showing a character

from a dominant group proclaim in Anand Kumar’s presence that social divides

are written into ancient scriptures and epics, since this is in truth how upper

castes continue to justify their claims to supremacy (the Censor Board forced

the producer to dub over the word “Ramayan” in that scene, and what we hear is

the person saying “Rajpuraan”). Bravo for having a poor, lower-caste postman

tell a post-office employee named Trivedi to quit his fossilised thinking and

realise that we live in an age when talent, not heredity, will determine who

rules. Bravo for the poor man who describes an inconsiderate medico as a

“donation-waala doctor”, because those opposed to SC/ST reservations use

“quota-waala” as an epithet and claim that meritocracy is their only concern

but do not raise similar objections to academic institutions in which

privileged classes can buy admission. Bravo.

(Applause fades) There is no explanation

though for why Anand’s caste is never specified in the film but only implied

through conversations in more than one scene. It remains the elephant in the

room whose presence has been alluded to but not stated in black and white. That

Which Must Not Be Named. But why?

Writer Sanjeev Dutta also

confuses class with caste when he shows the snobbery of Anand’s upper-caste

girlfriend’s father melt away as soon as the boy starts making big money. The

point about caste is its permanence, the fact that you cannot rise up a ladder

and shrug off the label that was pasted on you at birth even if you exit

poverty and illiteracy through hard work. Considering that the Dad had already

had a conversation with Anand in which he condescendingly referred to “your people”,

it seems unlikely that this man would forget his contempt overnight because

that is not what we see happening in the real India.

Super 30 is based on the life of mathematician-educationist Anand Kumar from Bihar. This is a

highly fictionalised account, as you will gather if you read media reports

about Kumar starting from the 2000s. It is also an account that steers clear of

all question marks raised in the media about Kumar, but since those question

marks themselves are murky and require a thorough investigation by an unbiased

reporter on the ground, I am not going into a comparison between the film and

reality.

Roughly speaking, Anand in the

film, like the real guy, is a mathematical genius whose academic brilliance

gets him admission in Cambridge University. His impoverished family cannot

raise the funds to send him there though. A chain of circumstances leads Anand

to a coaching institute for IIT JEE aspirants where he becomes a star teacher

and starts raking in good money. However, he decides one day to give up his

increasingly comfortable life and set up a free coaching school for under-privileged children where he

will train 30 chosen ones for the IIT entrance exam each year, providing them

with food and a house for an entire year as he trains them. He calls it Super 30. This leads to a

clash between Anand and powerful players in the state’s coaching institute

racket.

With all its problems, there is a

certain poignance to the account of Anand’s early life as we witness the love

within his family despite their financial struggles, the endearing flirtations

between his father and mother, his father’s wisdom and mother’s joyousness, and

the malice of those who claim to care about the downtrodden but in fact only

care for their votes.

After Anand launches Super 30

though, the storytelling becomes as uneven as the film’s understanding of

caste, getting downright lacklustre in large portions. The director seems to

lose his grip on the narrative as it rolls along, and it does not help that

Roshan’s performance is patchy at best. This is not even counting the fact that

at 45, the actor is playing a character who is in his teens at the start of

this film and in his 20s through most of the rest of it. This is also not

counting the fact that Anand in the late 1990s is styled to look like a

character out of a K.L. Saigal movie.

Few Bollywood stars can summon up

pain in their eyes as Roshan can, but there is a tone and mannerism he used in

his performance as a mentally challenged youth in Koi Mil Gaya (2003) that creeps into his dialogue delivery and

occasionally even his facial expressions here in Super 30 too. It is a tone he has dipped into each time he has been

called to portray simplicity in his career – in earlier roles it usually came

up just in passing and was therefore tolerable, but it is hard to ignore in

this film in which simplicity is the cornerstone of his character.

Hrithik Roshan is a gorgeous

looking man but he has always needed a firm directorial hand to guide him. His

Dad Rakesh Roshan, Khalid Mohamed (Fiza),

Karan Johar (K3G), Ashutosh Gowariker

(Jodhaa Akbar) and Zoya Akhtar (Luck By Chance, Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara) have brought out the very best in him.

Vikas Bahl has not.

The supporting cast of Super 30 is better. Mrunal Thakur, who

was excellent in Tabrez Noorani’s Love

Sonia last year, is given little to do as Anand’s girlfriend here, but she

pulls off that little well. The child actors are saddled with unmemorable

characters that have no depth or

expanse, but show flashes of how good they might be in better written roles.

Aditya Srivastava is solid as Anand’s unscrupulous professional rival. Sadhana

Singh and Virendra Saxena are absolute darlings as Anand’s parents. And Pankaj

Tripathi as a corrupt politician manages to be both hilarious and menacing at

the same time.

Once the script and direction of Super 30 begin to wander all over the

place, there is no turning back. For a start, no one on the team seems to have

stopped to ask how Anand intended to sustain Super 30 after exhausting his

savings. The real Anand Kumar runs a parallel coaching centre from which he

earns high fees that he then pumps into his classes for the poor, but there is

no mention of it here nor of any other source of income, perhaps because that

coaching centre has been a subject of some controversy. The director’s lax grip

on the reins screams out most in the scene featuring the children singing the

song Basanti No Dance that was

clearly designed to be moving but is curiously emotionally cold.

Ajay-Atul’s music deserved a

sturdier platform. As things stand, it is one of the best things about Super 30. Basanti No Dance and Question

Mark have an attractive beat and rhythm. Jugraafiya, with its lyrics by the inimitable Amitabh Bhattacharya,

is entertaining. And the end credits roll on a haunting melody titled Niyam Ho.

Super 30 comes across as a project that

someone somewhere lost interest in at some point and then it all came apart.

What else but casualness can explain the misspelling of the production house’s

own name in the final credits?

Director Vikas Bahl’s Super 30 comes to theatres in the shadow of an allegation of sexual violence against him that emerged in October 2018 in

the wake of the Me Too movement in Bollywood. Bahl’s decline as a filmmaker

began long before Me Too though with the release of the boring as hell Shaandaar starring Alia Bhatt and Shahid Kapoor in 2015. It is hard to imagine that the man who made the fabulous Queen (2014) starring Kangana Ranaut

also made Shaandaar. Frankly, with

all its failings, Super 30 is a

qualitative step up for him.

Bahl’s new film is not

insufferable and soporific like

Shaandaar, but it is misleading to

mention it in the same breath as Anubhav Sinha’s Article 15, as I did in the first paragraph of this review, without

a clarification. Article 15 is a

deeply affecting study of a police officer whose caste privilege has given him

the luxury of growing up ignorant about caste until it is rubbed in his face in

his adulthood, at which point he sets out to educate himself through

interactions with his colleagues and a Dalit activist. Caste should have been

omnipresent in Super 30 but by the

film’s second half has become almost an aside while the good folk battle

conventional Bollywood villains. Someone somewhere gave up on Super 30 a while back, and it shows.

Rating (out

of five stars): **

|

CBFC Rating (India):

|

U

|

|

Running time:

|

154 minutes

|

This review has also been published on Firstpost:

Visuals courtesy:

I felt the makers messed up with the subject (which was promising), had the direction and the editing been good, the end product could have been much better. Hrithik did put up a good performance but his Bihari accent wasn't that convincing.

ReplyDelete