The Kumbalangi Nights Phenomenon: One small step for Mollywood,

a giant leap for Indian cinema

By Anna M.M. Vetticad

It is now in its

12th week in Kerala movie theatres despite the tsunami effect that Avengers: Endgame has had on most small

films, it played for 7 weeks each in Chennai and Bangalore, 6 weeks in Mumbai

and Hyderabad, and 5 weeks in the National Capital Region – this is the kind of

pan-India spread and longevity that Kollywood, Tollywood and Bollywood’s

flamboyant star-laden big-banner ventures hope for but rarely get. Yet the film

we speak of here is not a mega project from one of India’s three largest industries,

but a little gem called Kumbalangi Nights

from the comparatively small Malayalam film industry a.k.a. Mollywood.

Made on a budget of

Rs 6.5 crore, Kumbalangi Nights sold

its overseas rights for Rs 1.5 crore and had grossed Rs 27.89 crore by April 4

from the box-office across India, according to its producers – it is likely

to cross trade pundits’ earlier expectations that it would close at Rs 30

crore-plus. Kumbalangi Nights has

none of the grandiose dialogues and lionising camera angles that characterise

films starring Mammootty and Mohanlal who continue to dominate Mollywood and

rake in big bucks in far larger quantities. Its appeal lies instead in its

simplicity and endearing slice-of-life tone mirroring the low-key tenor and

realism of the cinema that some observers have come to see as a Malayalam New

Wave of the past decade.

These films have

been varied in their ambition, storylines and scale but have in common their

desire to keep it real, to capture the flavour of the people and the fragrance

of the soil in which they are set. Such as in that moment in Kumbalangi Nights in which the

curly-haired Babymol (Anna Ben) shakes her head ever so slightly sideways in

vintage Malayali style, as she tells her friend in a sing-song Malayalam accent:

“Bobby and Baby – those names would look so good on a wedding card, would they

not?”

Or later when Babymol

has a tiff with Bobby (Shane Nigam) who storms off and boards a boat to escape

her, at which point she yells across the pristine water: “I have found a name

for a film about my life – Oolaye Premichcha Pennkutty (The Girl Who Fell For An Idiot).” And in the

background of that soundscape ruled by stillness and quiet, we hear the boatman

giggle.

Everyday lines such

as these spoken by Baby & Co. have attained iconic status among audiences

in the nearly three months since Kumbalangi

Nights’ release. Their allure comes from their ability to transport viewers

to the Kerala of reality, peopled by individuals and communities that tourists

can expect to bump into on a visit, unlike the make-believe world of

larger-than-life Mollywood ventures.

Kumbalangi Nights revolves around brothers

Saji, Bonny, Bobby and Frankie from the rural island of Kumbalangi on the

outskirts of Kochi. The siblings have a testy relationship. When their paths

cross with Baby, her sister Simi and autocratic brother-in-law Shammy, warmth

and a parallel discomfort are followed by self-loathing, conflict, mayhem, and

finally, redemption and reconciliation.

“I was absolutely

charmed by the story of a dysfunctional family like no other and the setting,”

says journalist Aseem Chhabra, director of the New York Indian Film Festival

who divides his time between India and the US. “The sense of simplicity

appealed to me. And gosh, it was so romantic.”

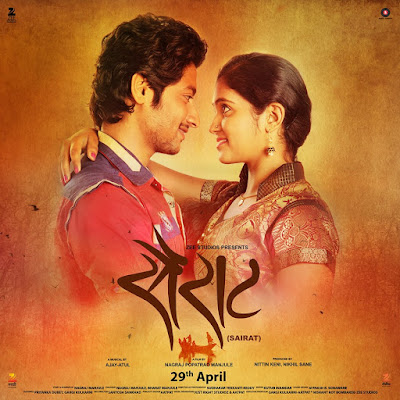

Humour, socio-cultural detailing and unobtrusive political statements are the qualities that have made Kumbalangi Nights a darling of critics and viewers. Collections apart, the film has acquired a pan-India cult following comparable to the respect earned by the Tamil film Aaranya Kaandam (2011), Thithi (Kannada) and Sairat (Marathi), both from 2016, and Malayalam cinema’s own Angamaly Diaries (2017).

This though is not

an account of Kumbalangi Nights’

success alone, but a chronicle of the position at which Indian cinema finds

itself right now as exemplified by the journey of this particular film.

Although the

exhibition sector nationwide has opened up considerably in recent years, vast

tracts headquartered in Delhi and Mumbai continue to treat non-Hindi Indian

cinema as subordinate to Bollywood and Hollywood. This pro-Bollywood/Hindi

slant led the Maharashtra government, for instance, in 2015 to make it

mandatory for the state’s multiplexes to slot at least one Marathi film during post-noon

hours.

Tollywood’s Baahubali franchise strategically surmounted this Bollywood bias by getting Bollywood stalwart Karan Johar on board as a presenter-distributor of its Hindi dubbed versions. It

was a giant-sized project anyway, but Johar’s association with it made it even

bigger because of his clout with northern and western Indian theatres and

with the ‘national’ media that is otherwise indifferent to Telugu cinema.

Despite the

self-defeating resistance from the exhibition sector that contradicts its own

expansion efforts, a Kumbalangi Nights

was inevitable for Mollywood on a landscape where scores of viewers

nationwide are demanding more than they have been served in previous decades

and the snail’s-paced leviathans of India’s film industries – producers, distributors

and exhibitors – have been gradually waking up to that demand.

In that sense, Kumbalangi Nights is the right film at

the right place at the right time.

Leading the

confluence of factors that has led to its triumph is the journey of Malayalam

cinema along two co-existing tracks. On the one hand Mollywood churns out

bombastic big-budget films like this summer’s Madhuraraja starring Mammootty and the Mohanlal-starrer Lucifer that have created a storm at

turnstiles in Kerala and among Malayali fans of these stars outside the state.

On the other hand are mood films occupying the same plane as Angamaly Diaries and Kumbalangi Nights – Ustad Hotel, Kammatipaadam,

Maheshinte Prathikaaram, Take Off, Mayaanadhi, Eeda and Koode among them – that have in the past

10 years or so sustained Mollywood’s nationwide reputation as a maker of

quality realistic cinema that does not necessarily head off into overly artsy,

esoteric or dreary territory. Their middle-of-the-road nature – thoughtful yet

entertaining in varying ways – has earned them a loyal following not just

among Malayalis, but also among non-Malayali cinephiles.

Kumbalangi Nights’ debutant director Madhu

C. Narayanan acknowledges the debt of gratitude that filmmakers like him

owe Kerala audiences who have nurtured this movement. “When we made Kumbalangi Nights,” he says, “we did it

with the absolute confidence that at least we were guaranteed the audience that

had seen Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum.”

Narayanan was credited for “creative contribution” in the latter, director

Dileesh Pothan’s National Award winning hit from 2017.

It’s a classic

chicken-and-egg situation: as a new lot of experimental Malayalam filmmakers

like Aashiq Abu and Pothan emerged, viewers hungry for a change from formulaic

fare backed them, and these filmmakers returned the favour by taking bigger

risks and persisting in making formula-defying films not reliant on reigning megastars,

thus whetting existing viewer appetites while simultaneously generating

curiosity among others and drawing more people to their works day by day. “With

each passing film, the audience for such cinema has increased,” Narayanan adds.

“The fact that there is a ready audience for quality cinema in Kerala gives us

the confidence to explore more such unusual subjects.”

This confidence

complements the digital upsurge that has revolutionised entertainment in India

in recent years.

Until about a decade

back, conventional ‘wisdom’ in the film exhibition and distribution trades

largely assumed that the only Indian films (other than Hindi) that Indians were

interested in watching were in their own respective mother tongues. This myopic

attitude did not take into consideration people who had for years been visiting

film festivals, joining film clubs, buying DVDs or illegally downloading films

online in various languages since their local theatres denied them the variety

they craved. In the case of films in languages other than Hindi, this group of

committed cinephiles was mostly deemed by decision makers to be too

minuscule to translate into significant box-office collections if the same

films were to be given theatrical releases outside the regions in which their

languages are primarily spoken. Barring exceptions such as the multiple dubbed

versions of Mani Ratnam’s Roja and Bombay released in the 1990s, little

effort was made to build awareness and spur audience growth by resorting to

dubbing and/or subtitling and strong marketing.

Producers of films

in languages other than Hindi either had a frog-in-the-well attitude and/or

were weighted down by a defeatist, fatalistic assumption that they did not

stand a chance pan-India. They also faced – and still do – the hurdle of an

unabashed pro-Hindi/Bollywood bias in the supposed ‘national’ newspapers and TV

channels based in Delhi and Mumbai, a bias that automatically drastically cuts

down the number of news platforms on which these films could be promoted.

(Note: Bollywood

producers too lacked – and still lack – the vision to subtitle their films in a

bid to expand the viewership they already garner outside Hindi-speaking

regions. Despite the privileges they enjoy, industry insiders estimate that on

an average only 30 per cent of Hindi film collections come from beyond the

Hindi belt, so there is indeed scope to extend their reach.)

It did not help

that in the pre-digital age of physical prints, dubbing and/or subtitling was

logistically tougher. India’s film industries lacked the far-sightedness to

realise that the additional inconvenience and investment involved would lead to

a long-term widening of audiences for cinema across Indian languages.

Hollywood was much

quicker to nose out the potential for its films beyond the traditional audience

of English speakers in India. It has been about 20 years since American majors

made it a standard practice to release their films – all the tentpole projects

and many smaller ones – in dubbed Telugu, Hindi and Tamil versions in India in

addition to the original English.

“Hollywood had the

foresight to see that localisation was the way forward to expand markets,” says

Raj Malik, Vice President – Strategy & Business Development of the

Mumbai-based Inspired Entertainment, a content production, distribution and

promotion company. An industry veteran who has previously held senior positions

at Warner Bros, Eros and Disney in India, Malik recalls that from the late

1990s onwards, long before Indian audiences for Hollywood films had reached the

size they are at today, “India offices of the big studios were carpet-bombing

the market with dubbed content, ranging from Men in Black to Night At The

Museum, from superhero adventures to animation features”. He adds: “Films

like those of the Marvel Cinematic Universe have achieved their present scale

because of the years invested in building and enlarging the worldwide audience

for them in this fashion.”

India took a cue

from Hollywood much later. In the past decade or so, accompanied by the mushrooming

of multiplexes, there has been an increase in Indian language cinema other than

Hindi (let’s avoid the marginalising term “regional cinema”, please) being

released outside their home bases. Quite fortuitously, the TV media explosion

at the turn of the century had led to Hindi dubbed versions of southern Indian

films being regularly released on general entertainment channels, which familiarised

Hindi audiences with the stars of these industries, thus piquing the interest

of some of them at least to sample these films in their original languages

whenever they were available with subtitles – the gains in audience numbers in

theatres have been a steady trickle ever since.

The more recent

rise of the social media has also helped spread the word among film buffs about

good cinema across languages that the mainstream news media in the north was/is

not covering. The advent of online news platforms has helped too – news websites

have by and large been more open-minded in this arena than newspapers and TV

channels. At the same time, as theatres have gone digital, the switch to

digital prints from physical prints has made subtitling easier.

Mangesh Kulkarni, Business

Head of Zee Studios’ Marathi division points out that digitisation has also

simplified distribution. “Earlier one had to take prints physically to certain

markets, which is no more needed,” he explains. “This is helping us open more

territories more feasibly and faster. We are able to catch on another territory

while the buzz about a film is very high.”

The road is still

long and wearying because the birth of new media and new technology has not

necessarily been accompanied by new mindsets in all quarters. So, even today

not all producers subtitle their films. Booking websites and listings do not

give information about subs. Theatres – including India’s biggest multiplex

chain, the PVRs – routinely provide wrong information about subtitles on their

helplines and at booking counters. And even when films are subtitled, these theatres

often simply skip playing the subs.

This lethal combination of inefficiency, systemic failings, cultural insularity and short-sightedness has persistently stood in the way of all Indian cinema being available to all Indians, yet there has been some notable forward movement on this front. Rajinikanth-starrers, for one, have got bigger and bigger releases outside southern India, in dubbed versions and in the original Tamil, ever since Sivaji caught the imagination of the ‘national’ media in 2007. And though blockbuster status in every corner of the country remains uncommon even for Hindi with all its advantages, a pioneering distribution and promotional gameplan helped the Baahubali franchise – dubbed versions and the original Telugu – to slip through the cracks, ace all hurdles and achieve that rare distinction, with Baahubali: The Conclusion becoming the highest grossing Indian film of all time and Baahubali: The Beginning too ranking among India’s Top 10.

These however are

projects with large budgets mounted on a massive scale, designed as mass

offerings and with the wherewithal to market themselves heavily. Arguably the

more heartening development of the past decade has been the emergence of

smaller filmmakers and smaller, thought-provoking films in various languages

other than Hindi impacting the pan-India box-office when released with

subtitles. This has been enabled, among other things, by social-media-driven

word of mouth and the economics of multiplexes, which allows space for films of

all sizes.

Riding this trend,

directors like Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni (Marathi), Lijo Jose Pellissery

(Malayalam) and Raam Reddy (Kannada) have become familiar names among committed

cinephiles countrywide with their intimate portraits of specific cultures.

Nagraj Manjule (Marathi), Anjali Menon (Malayalam) and Rajeev Ravi (Malayalam)

appear to have cracked the mystery of how to turn realistic, issue-driven cinema

into large-scale money-spinners. They are all children of an evolving consumer

whose existence is slowly compelling Indian producers, distributors and

exhibitors to rethink their business plans.

Online platforms on

their part have had a dual revolutionising effect on audiences: at one level,

they offer easy access to films that were earlier hard to come by

for those viewers who never considered language a barrier, at another

level they serve to educate new audiences through exposure. This, film industry

watchers believe, is further raising footfalls in mainstream theatres for cinema

in languages other than viewers’ mother tongues, which demand is then

translating into more shows for such cinema in theatres.

“The digital media

are preparing people en masse for consumption of content whether it is in their

language or any other language with subtitles,” says Zee’s Mangesh Kulkarni

The Marathi film industry, which rivals Mollywood’s reputation for quality, is a good case study here. Kulkarni says that earlier a Marathi movie’s average collections outside Maharashtra would be 5% of the total, but that has changed in recent years with films like Katyar Kaljat Ghusali (2015) and Natsamrat (2016). Small, meaningful Marathi cinema already had a dedicated audience outside the state and beyond Marathi speakers, but the scale of interest in Marathi cinema at large has shot up since Sairat, Nagraj Manjule’s 2016 film about an upper caste girl and a Dalit boy in love: 12% of Sairat’s total collections came from outside Maharashtra, the figure was 10% for last year’s parent-child saga Naal and Anandi Gopal, a biopic of one of India’s first woman doctors.

“The market for

Marathi movies outside Maharashtra was earlier in pockets with primarily

Marathi populations. These last few films have broken that,” says Kulkarni. Naal “had a 3-4 week run in Chennai”,

while Anandi Gopal “has done

exceedingly well in Hyderabad, Bangalore and Kolkata. They were not

necessarily watched by Marathi folks, they also got huge acclaim from

non-Marathis in those areas.”

Kumbalangi Nights’ Madhu C. Narayanan

believes video online streaming platforms not only feed intelligent,

adventurous audiences, they have also made audiences at large more exacting. “Unlike

in our youth, today young people have plenty of opportunities and platforms in

their hands to watch films of all languages from across India and the world,”

he explains. “When youngsters with exposure to so much quality cinema watch our

films, we too have to compulsorily maintain a certain minimum quality.”

It is in this

context that Kumbalangi Nights has

been embraced by cineastes across the country. As it heads for

Delhi’s Habitat Film Festival in May, this film is a timely reminder that while

language maybe region specific, emotions and laughter are not.

The country’s

film-crazed millions can only hope that their own increasing open-mindedness

and this era of online video streaming will deal a final death blow to the

misconceptions, prejudices, lack of enterprise and inefficiencies that

have for decades stalled the spread of India’s own cinema within

India.

This

article was published on Firstpost on April 30, 2019:

https://www.firstpost.com/entertainment/the-kumbalangi-nights-phenomenon-one-small-step-for-mollywood-a-giant-leap-for-indian-cinema-6543241.html

Photographs courtesy:

(5) Zee Studios

No comments:

Post a Comment